Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott calls the overrepresentation of Indigenous children and youth in government care a “humanitarian crisis.”

National data on kids in care is hard to come by as child welfare is a provincial and territorial responsibility. However, the most recent census found 52 per cent of kids under 15 in foster homes are Indigenous.

Yet Indigenous children are just under eight per cent of the under-15 population in Canada today.

More than 90 per cent of Manitoba’s 11,000 kids in care are Indigenous. In B.C. 64 per cent of our 6,804 kids in care identify as Indigenous, even though they make up just under 10 per cent of the population under 19.

The outcomes for kids in the child welfare system, Indigenous or not, are not good. In British Columbia, kids in care are more likely to wind up in jail than they are to graduate high school. Across Canada, kids in and from the foster care system make up 60 per cent of homeless youth, and a third of our homeless adults.

For Indigenous youth, the issues are worse. Placements with non-Indigenous families separate them from their communities, and even expose them to denigration of their culture. That’s compounded by the intergenerational trauma many experienced in their birth families stemming from colonization, the residential school system and the mass adoptions of their parents and grandparents in the Sixties Scoop.

While Philpott is the first federal minister to declare it a humanitarian crisis, the government has known about this injustice against Indigenous communities for at least 40 years.

In 1977 representatives from the federal government, Manitoba and the Manitoba Indian Brotherhood formed the Indian Child Welfare Sub-Committee to examine why 60 per cent of kids in care in the province were Indigenous — First Nations, Inuit or Métis.

Status First Nations children alone made up 29.9 per cent of children in care in Manitoba in 1979. Provincial officials estimated they took 600 to 700 status First Nations children into care every month. (The province did not track the number of non-status Indigenous children taken into care.)

Governments haven’t just known about this crisis for four decades, says Shelly Johnson, assistant professor of education at Thompson Rivers University and a former child welfare social worker. They created and perpetuated a system that keeps Indigenous kids in government care.

“The whole system was established to maintain control over Indigenous people,” said Johnson, a Canada Research Chair in Indigenizing Higher Education. “When you have Indigenous children in your care and custody, you have all the power over that family.”

Every province and territory makes its own decisions on child welfare, including for reserve communities. So how did they all end up with an overwhelming number of Indigenous children in care?

Like every social issue facing Indigenous people in Canada, the origins date back to colonization.

The earliest settlers’ writings show their misunderstanding of Indigenous child-rearing and how their feelings of racial and cultural superiority clouded their judgments.

Early missionaries saw First Nations child-rearing practices as “negligent, irresponsible and uncivilized” because they refused to physically punish their children and respected them as individuals, instead of seeing them as clean slates on which to write.

Settler governments viewed Indigenous people, adults and children, as wards of the state. The 1876 Indian Act, as Manitoba’s Aboriginal Justice Implementation Commission would conclude more than a century later in 1991, effectively gave government control over First Nations people’s lives, dictating where and how they would live, hunt, work and play.

And how their children would be raised. Three years after the Indian Act was passed, then-prime minister Sir John A. Macdonald sent MP Nicholas F. Davin to the United States to study its system of industrial boarding schools for Native American children.

Inspired, Davin recommended Canada adopt the assimilation model. “If anything is to be done with the Indian, we must catch him very young,” his report said. “The children must be kept constantly within the circle of civilized conditions.”

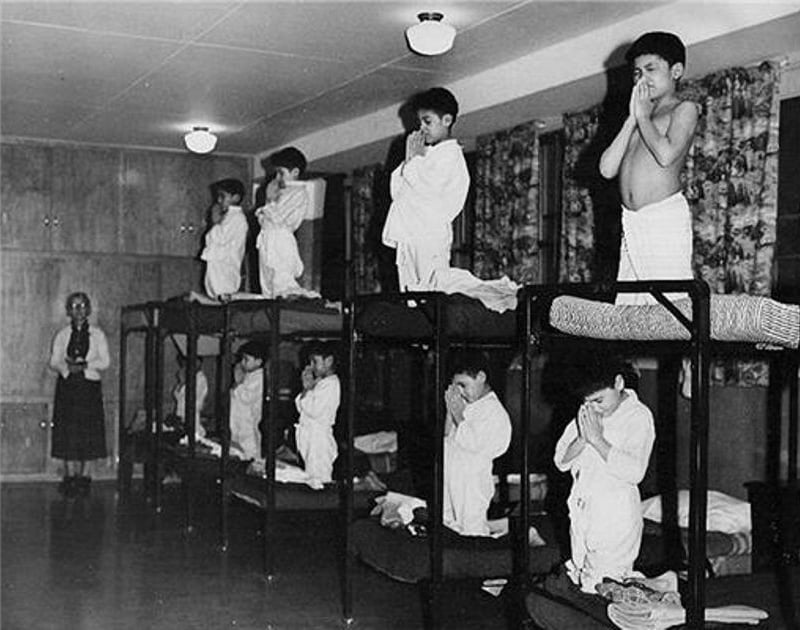

Within a few years, the first Canadian residential schools opened. There were 136 schools in all, and about 150,000 children, mostly First Nations, but also Inuit and Métis, attended a residential school.

In 1920 the federal government made attendance mandatory for status First Nations children, a rule that remained in place until 1951. Church control over the schools ended in 1969 when jurisdiction was transferred to the federal government, which began winding the project down in the 1970s, closing the final school in 1996.

First Nations people began rejecting residential schools in the 1950s, says Raven Sinclair, associate professor of social work at the University of Regina. The buildings, unsuitable in the first place, were crumbling and stories of abuse — sexual, physical and mental, by teachers, administrators, and even fellow students — were emerging.

“At the same time, schools of social work in Canada were starting to pump out social workers,” said Sinclair.

“We had cohorts of social workers coming out in the late ’40s and into the ’50s. I think they probably needed something to do.”

At the same time, there was increasing public awareness of the deplorable living situations on reserves — although without any context on why poverty, poor housing and sanitation, substance abuse and violence were omnipresent.

“After five generations of being in residential schools caused such tremendous harm, that people took this harm back to the community,” said Sinclair, a member of the Gordon First Nation whose great-great-grandfather was the first member of her family to attend residential school.

“So there were lots of issues in communities: divisiveness, social conflict, interpersonal conflict,” she said.

“And humans being who we are, no matter what sort of trauma we’ve been through, we continue to have babies. So residential school survivors had children, and this is where the abuse started. There were very few families that escaped that type of socialization in the total institution in the schools. The socialization of trauma and abuse.”

In 1947 two groups representing social workers — Canadian Welfare Council and the Canadian Association of Social Workers — had told a parliamentary committee that they had the solution: change the Indian Act to allow provincial social services delivery in federally controlled First Nations communities.

Referring to status First Nations people in their brief as “wards” of the state, the social workers asserted that “Indian children who are neglected lack the protection afforded under social legislation available to white children in the community.”

The submission also took issue with sending “neglected” children to residential schools. But their solution had the same aim of removing the children from their community, family and culture by putting them in non-Indigenous foster and adoptive homes.

In 1951 they got their wish. The federal government amended the Indian Act to transfer jurisdiction for on-reserve social services to the provinces. But the change did not include any transfer of funding to the provinces, something that wouldn’t happen until the Canada Assistance Program was introduced in 1966.

The number of Indigenous kids in care grew exponentially from that point on. In 1955, for example, Indigenous kids made up less than one per cent of the 3,433 kids in B.C. government care. By 1964 there were almost 1,500 Indigenous kids in care, just over one-third of all kids in care.

Nationwide the numbers followed a similar pattern.

“In the ’50s it was one-point-something per cent. Then in the ’70s it was around 20 per cent,” said Johnson. “Then in the ’80s was really when I think the population was probably 40 per cent. In the early 2000s it was over 50 per cent, and it’s still that now.”

Not only did social workers in the 1950s and ’60s not understand why families on reserves lived in such dire straits, they had no idea what a healthy Indigenous family looked like.

“The social workers, most of them were coming from white upper-middle class homes and living in urban centres in Canada where the universities were, and had never been out on the land, let alone encountered Indigenous people,” said Sinclair.

“They were looking at assessing situations through their own Eurocentric view, and might go into a house on the reserve, it might be a cabin, and their eyes weren’t trained to see the types of food that might be in that house.”

Sinclair is widely recognized as an expert on the Sixties Scoop, when thousands of Indigenous children were taken into care across the country. While her education and research credentials are impressive, it’s her firsthand experience as a child taken from her mother in the 1960s that drove her to find out more about what she now refers to as the Indigenous Child Removal System in Canada. Sinclair was separated from her older sisters who went into foster care, while she was adopted, along with her two younger brothers, by a non-Indigenous family.

“My mother had no idea what was going on, she never gave her consent. Never signed anything, but I was made a Crown ward because they chose me out of a selection of children that had been advertised for adoption,” she said.

“Probably the worst thing to happen to human beings is to have your children taken from you. It’s a horrible thing beyond imagining.”

How the Sixties Scoop happened

In the early 1980s Patrick Johnston headed a Canadian Council on Social Development research project into why there were so many Indigenous kids in care. His interview with a B.C. social worker about her role in the 1960s is credited for coining the term “Sixties Scoop.” The worker and her colleagues would “quite literally, scoop children from reserves on the slightest pretext,” Johnston wrote in his subsequent book based on his research, Native Children and the Child Welfare System.

“She also made it clear, however, that she and her colleagues sincerely believed that what they were doing was in the best interests of the children.”

Brad McKenzie, now professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba’s school of social work, is largely credited, along with his co-author Pete Hudson, as one of the first non-Indigenous people to link the high rate of Indigenous kids in care to an ongoing process of colonization.

“The antecedents were the medical system, the residential school system, and even beyond that a profound history of colonization and subjugation that is interrelated with institutional racism,” McKenzie said.

The work by McKenzie, Hudson and Johnston did manage to draw attention, at least in the child welfare sector, to the issue in the 1980s.

Johnston was told his research for the book, which included surveying child welfare agencies in every province and territory and interviewing Indigenous elders and families, was the impetus for Manitoba’s Kimelman Inquiry, which began in 1982 and went on to expose the practice of sending Indigenous children in the province to be adopted by non-Indigenous families in the United States, a practice that had also previously occurred in other provinces.

But Johnston’s nationwide book tour following Native Children’s release in 1983 failed to draw much in the way of media or public attention.

“There were other more pressing issues, I guess, from the point of view of provincial governments,” he said, adding both federal and provincial governments were well aware of the issue of overrepresentation.

“And Indigenous communities had other real challenges, as well, that they were struggling with. There’s probably a multitude of reasons we started off with some hope 40 years ago and sort of disappeared off the radar screen 30 to 35 years ago.”

McKenzie isn’t surprised the issue didn’t take off in the 1980s. “It’s rare for governments to take particular direction from one piece of information, or sometimes a lot more than one research study about those issues. It takes a lot of data, a lot of pressure and a lot of activism to change those points of view,” he said. Most of the credit for raising the alarm goes to Indigenous people, he added.

Assistant Chief Justice Edward Kimelman’s final report on the adoption of First Nations and Métis children outside the country said that the child welfare system was an act of “cultural genocide”: “In 1982, no one, except the Indian and Métis people, really believed the reality — that native children were routinely being shipped to adoption homes in the United States and to other provinces in Canada. Every social worker, every administrator, and every agency or region viewed the situation from a narrow perspective and saw each individual case as an exception, as a case involving extenuating circumstances. No one fully comprehended that 25 per cent of all children placed for adoption were placed outside of Manitoba. No one fully comprehended that virtually all those children were of native descent.”

Thirty-six years later, the federal government publicly acknowledged the overrepresentation of Indigenous kids in care is a crisis.

Coming Monday: In part two, how poverty, underfunding and a lack of Indigenous control helped create a child welfare crisis.

https://thetyee.ca/News/2018/05/09/Canada-Crisis-Indignenous-Welfare/?utm_source=weekly&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=140518

Recent Comments

Recent Comments Easyfinancefirm (@ gmail. )com,..….............

Easyfinancefirm (@ gmail. )com,..….............

As an Indigenous person and a granddaughter of Residential Survivors, I wouldn’t be here today, attending school to become a Social Service Worker. The topic of “crisis” is still very real in Canada, let alone in Ontario, my people are still struggling with substance abuse, alcoholism, and generational trauma. I thank my grandparents for not falling into the alcoholic lifestyle after residential school but working hard to provide for their families. I wouldn’t be living the lifestyle I have because I was raised by parents who worked and supported their families. And that’s exactly what I want to continue to do, work hard, support my people, and to know that I will be a small piece of change for indigenous people all around. I want to be a supportive social worker as an indigenous person helping Indigenous youth find their roots in a traditional path. Guiding them with giving them the opportunities to learn many different lands base teachings. Support their journey of becoming men and women, understanding the teachings that come with their changes. There’s so many programs being offered for indigenous people, these are opportunities for social workers to take part in to help themselves understand who they are working with. It also will help me grow more in the knowledge of my roots as an anishnawbe person. I will forever be proud of all anishnawbe people for attempting to find their roots or has started their sobriety with the support of Social Justice and Social welfare. I want to support and make a difference in someone’s life, to help them during their healing journey, after all our children are our future leaders of indigenous people.

The main thing I got to learn that how hard it would have been for Indigenous people to go through all of those things losing their children and the discrimination they endured, and they still have to suffer from all the colonialism and systematic racism. The article does give us a clear picture of the child welfare system towards the betterment of children but not as good for the indigenous people comparable to nonindigenous. I feel like the government should once rethink the effects the Indigenous people have to go through such as the intergenerational emotional psychological, and emotional traumas, and loss of culture and traditions. These things are leading to the disappearance of indigenous culture. Learning all things will help us to be more aware of the issues the children may be facing, That I am aware of what might have suffered or what led them to suffer, or if there are any other foreign family factors affecting them, it could have happened with an adult too. Looking after them and their mental health, respecting them more, respecting the thing that they are from an indigenous background, and helping them with a family who also respects similar feelings. Knowing that this is a crucial topic I would like to continue learning about it and respecting it more, providing my support, and also letting more people know about the harsh historical reality..

The information spoken about in “How Canada Created a Crisis in Indigenous Child Welfare” provides a clear description of how beneficial child welfare systems are as general, they are never good to begin with but when it comes to Indigenous children it’s even worse. There were many issues with child welfare with Indigenous peoples consisting of intergenerational trauma, abuse, loss of language and culture etc. These issues that are faced when children are young affect them even greater in adulthood, learning about the issues with child welfare in general especially relating to Indigenous peoples will make us all more aware of the issues and setbacks these children can have, knowing that they are struggling, needing to respect them, look after them as well as making sure their culture isn’t thrown out the window as soon as they step foot into a new home. Being knowledgable about the history of Indigenous peoples we all can do better to spread awareness as well as treating them like they are human because they are. This topic will overall reflect into my future of learning more about the Indigenous communities, what they need, how to support them, and how can we overall make their communities safer in general. As the topic of Indigenous peoples is sensitive in Canada, because of the history the country has created for them is disgusting, we all know better, and are taught the facts of how they have been treated and pushed to the side, acknowledging that Canada hasn’t tried to benefit them with several human basic rights, we need to make up for the intergenerational trauma that still affects children in todays society.