9 Times Canada’s Labour Movement Made History and Shaped the Country We Live in Today

PressProgress.ca – 9 Ttimes/Canada – Here are just nine examples where unions proved they have the power to make history.

September 4, 2017

Many students in Canada will be heading back to school after Labour Day.

But they might not spend much time talking about the history of Canada’s labour movement or their basic rights under existing labour laws – in much of Canada, this history has been glossed over or ignored, leading some academics to conclude “the Canadian worker has been a neglected figure in Canadian history.”

Except it’s not that hard to find examples of how the labour movement helped shape the country we live in today.

Whether they’re fighting for shorter work days or better wages, the labour movement has done more than just improve working conditions for ordinary people – by standing up to powerful elites, time and again, Canada’s labour movement set in motion series of events that changed the course of history and moved Canada forward.

Here are just nine examples where labour unions proved they have the power to make history:

Back in the 1870s, many Toronto printers worked shifts longer than 10 hours a day.

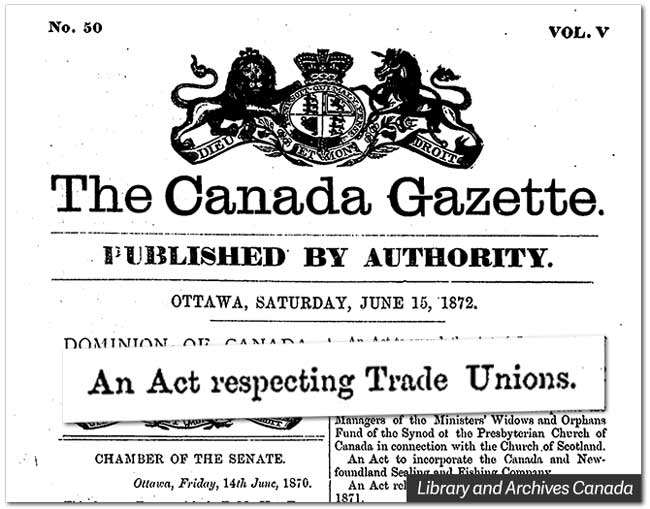

When the Toronto Typographical Union demanded a 9-hour work day in April 1872, the city’s publishers refused, so workers walked off the job – something that was considered a criminal act back then.

Over 10,000 people joined the striking printers on the steps of Queen’s Park, resulting in their employer agreeing to give them a shorter workday and forcing Prime Minister John A. MacDonald to quickly respond by introducing the Trade Union Act, legislation that legalized and protected unions.

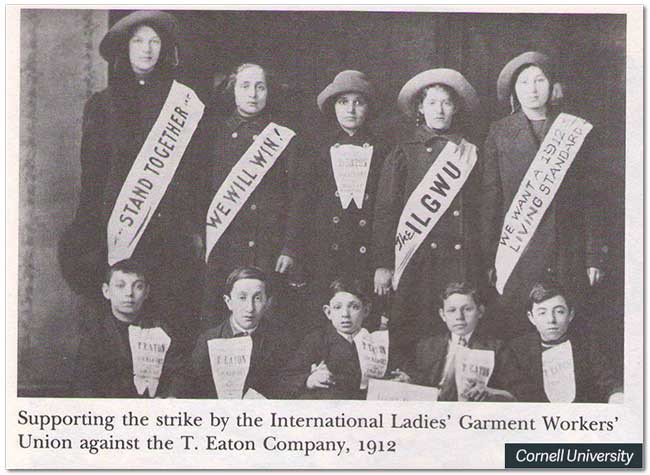

The factory floor at one of Canada’s largest department stores ground to a half in the frigid winter of 1912.

Male garment workers had been paid 65 cents per coat. Now they were being asked to do more tasks with no extra compensation and the women who had done them previously would go unpaid.

Eaton’s refused to negotiate with a union, and they locked out 65 men. Soon 1,000 other workers joined them in the streets, many of whom were women.

Despite widespread anti-Semitism, the predominantly Jewish garment workers organized a successful boycott against Eaton’s – one Yiddish slogan used by strikers translated as:

“We will not take morsels of bread from our sisters’ mouths.”

The strike gained popular support, bringing 2,000 people to a rally on March 23rd and represented a move towards breaking down divisions across lines of gender and ethnicity.

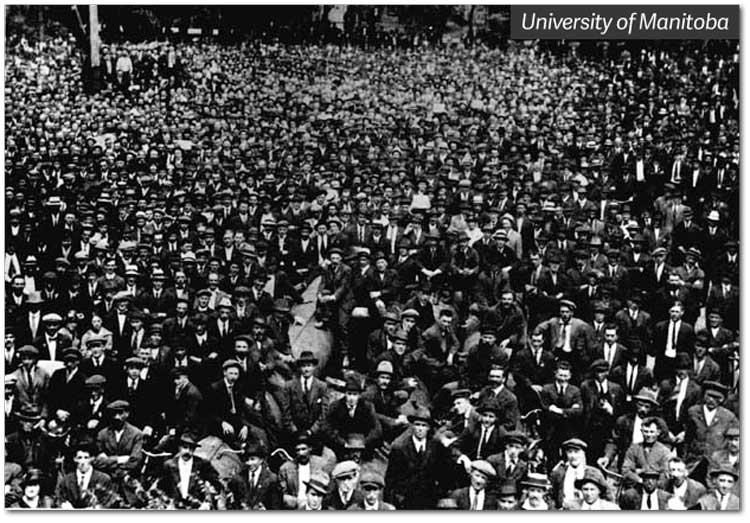

The Winnipeg General Strike remains the single biggest labour action in Canadian history to this very day.

It began on May 15, 1919 as nearly 30,000 workers walked off the job to strike for better wages and working conditions and were soon joined by public sector employees including police, firefighters, postal workers, utility workers and others.

Alarmed by the strikers, Winnipeg’s elite industrialists, bankers and politicians formed a committee that spread conspiracy theories and xenophobia through the city’s newspapers, attempting to divide workers and discredit the strike as a plot by foreign agitators and “alien scum.”

On what became known as “Bloody Saturday,” police charged a crowd of striking workers resulting in dozens of casualties and jailing prominent labour leaders like J.S. Woodsworth.

Although Winnipeg’s elites were successful at suppressing the strike, its legacy rippled through Canadian political history: Arthur Meighen’s Conservatives were decimated at the next election, Mackenzie King’s Liberals bent to pressure and implemented key labour reforms and Woodsworth would become the first leader of the CCF, precursor to the modern NDP – the strike was also left a life-lasting impression on the NDP’s first leader, Tommy Douglas, who watched the violence in Winnipeg unfold in-person as a teenager.

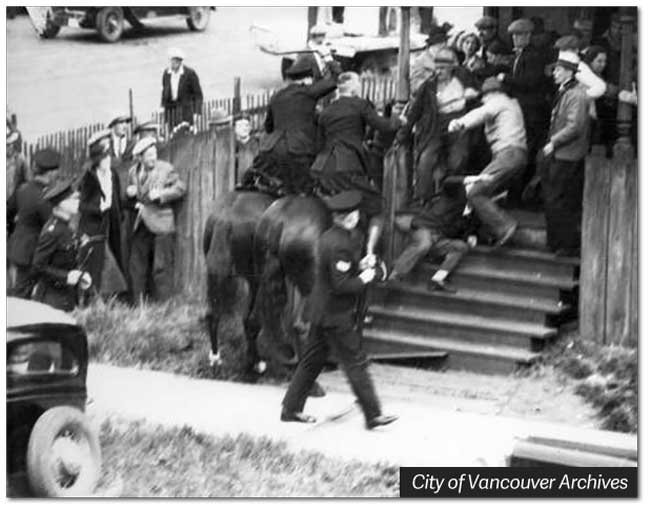

Inspired by striking counterparts at docks along the US Pacific coast in 1935, longshoremen in Vancouver walked out in support of workers in Powell River – where a non-union crew had been brought in to load a cargo ship.

Determined to crush the walkout, local employers and authorities turned to violence against 1,000 longshoremen and their supporters, marking the first time in Canadian history police used tear gas in a domestic setting:

“For the first time, tear gas was unleashed in Vancouver. The strikers quickly scattered. But that wasn’t enough. The police pursued them with a vengeance, bashing heads as they advanced. There are amazing photos from the day, showing horses charging up the street after fleeing protestors. One famous shot shows two police officers on horseback going right up to the steps of a house, clubbing defenceless workers as they tried to take refuge on the porch.”

Between the violence in Vancouver and the government’s handling of the “On-to-Ottawa” Trek, the labour unrest of the mid-1930s would contribute to the fall of R.B. Bennett’s Conservative government.

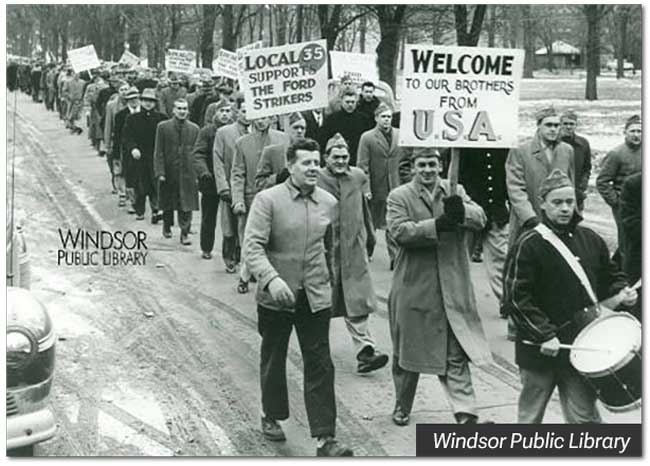

Employing 14,000 people, Ford’s Windsor complex was the biggest workplace in Canada in the 1940s after World War Two.

At the time, union membership wasn’t mandatory and the law prevented unions from automatically collecting dues from their members, putting the the union on a weak footing.

After Ford announced 1,500 layoffs, the United Auto Workers demanded mandatory membership for all workers employed at the auto plant. After a massive strike that included a show of solidarity from American UAW members, Canada’s federal government eventually bent to pressure and appointed an arbitrator.

The arbitrator, Supreme Court Justice Ivan Rand, would issue a historic ruling known as the “Rand Formula,” described this way by the Globe and Mail:

“The formula says that in a unionized workplace, employees are free to join or not join the union – but either way, they must pay union dues. That’s because every worker in a union shop, member or no, benefits from efforts made by the union in contract negotiations. The formula is meant to prevent anyone from getting a free ride.”

To this day, the Rand Formula remains a major obstacle for Conservatives who want to bring American-style right-to-work laws to Canada.

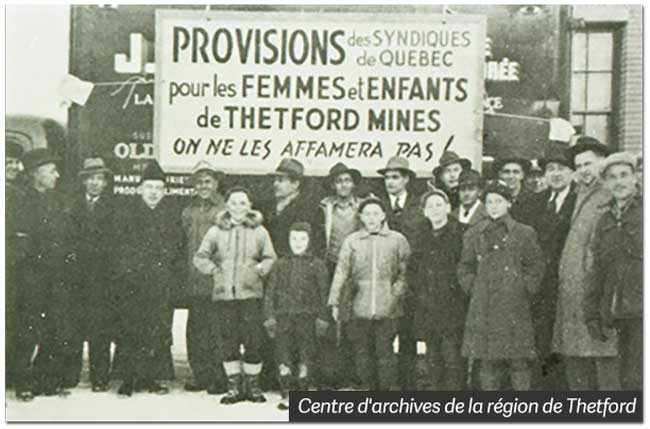

A decade before the Quiet Revolution, asbestos workers in 1949 shook the foundation of Maurice Duplessis’ ultra-conservative government and inspired a generation of political leaders in Québec.

The workers voted to strike, something that was illegal. They had straightforward demands: a $1/hour wage, union security, a pension scheme and company action in the face of health risks brought on by exposure to asbestos.

Violence erupted at the strike when the Anglo-American owner of the mine hired strikebreakers to replace the Francophone workers. Duplessis backed the American owner over the Québecois workers, causing the Catholic Church to break with Duplessis and triggering the beginning of a rift in Québec society.

The event is widely considered to be a key moment in Québec history and helped launch the political careers of Jean Marchand, Gérard Pelletier and former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau – Trudeau co-wrote a book reflecting on the strike, describing it as the “turning point in the entire religious, political, social, and economic history of the Province of Quebec.”

Even by the 1980s, paid maternity leave was rare – only a single union in Québec had secured that benefit at the time.

In 1981 following a successful 42-day strike, the Canadian Union of Postal Workers won postal workers across Canada 17 weeks of paid maternity leave – a concept which consequently became mainstream throughout the country.

Reflecting on the strike, CUPW National Representative Marion Pollack later remarked:

“It’s really a fundamental principle in terms of equality and in terms of the future of the society. We needed to address in our collective agreement the fact that women who decided to have children were being financially penalized for having children.”

Twenty-six miners were killed by an explosion at the Westray Mine in Plymouth, Nova Scotia on May 9, 1992.

This preventable tragedy provoked outrage across the country as a public inquiry blamed management, bureaucrats and provincial politicians.

Thanks to efforts by the labour movement, notably the United Steelworkers, and the families of those killed in the explosion, the federal government bent to pressure and introduced Bill C-45.

Also called “The Westray Bill,” C-45 created a legal duty for those who “direct the work of others” to ensure the safety of all workers and members of the public. It also established new sections of the Criminal Code under which corporations and their managers can be charged criminally for negligence.

Today, a diverse coalition of labour and its allies is mobilizing Canadians across the country to push back against “deteriorating” wages and demand a $15/hour minimum wage.

Not very long ago, hourly wages in some provinces were as low as $9/hour, despite the fact that skyrocketing costs of living in many cities mean you’d need double that to make ends meet.

Thanks to successful organizing, governments in three of Canada’s largest provinces – Alberta, Ontario and BC – are all in the process of implementing a new wage floor of $15/hour

http://pressprogress.ca/9_times_canada_labour_movement_made_history_and_shaped_the_country_we_live_in_today/

Tags: crime prevention, economy, featured, Health, jurisdiction, participation, rights, standard of living

This entry was posted on Wednesday, September 27th, 2017 at 11:00 am and is filed under History. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

One Response to “9 Times Canada’s Labour Movement Made History and Shaped the Country We Live in Today”

|

Leave a Reply

Recent Comments

Recent Comments

who are the most influential people in their movements?