What’s behind Canada’s housing crisis?

Posted on November 6, 2024 in Debates

Source: TheConversation.com — Authors: Hanan Ali, Yushu Zhu

TheConversation.com

October 3, 2024. Yushu Zhu, Hanan Ali

Experts break down the different factors at play

Canadians are in the grip of a deepening housing crisis, yet not everyone agrees on what exactly the housing crisis is. The common narrative focuses on an affordability crisis for homeownership, attributed to either excessive demand from immigrants and foreign buyers or a lack of supply.

Canada’s housing market is among the most unaffordable, with one of the highest house-price-to-income ratios among OECD member states. Housing prices soared over 355 per cent between 2000 and 2021, while median nominal income increased by only 113 per cent.

But today’s housing crisis extends beyond unaffordable homes and supply shortages. It’s rooted in a deeply financialized housing system that idealizes homeownership and treats homes as financial assets instead of social goods.

What is the housing crisis?

The housing crisis is not new in Canada. In his book on the evolution of Canadian housing policy, historian John Bacher describes that, in the early 1900s, Canadians were “faced with the choice of accepting shelter that was overcrowded, poorly serviced, or below minimal building-code and sanitary standards.”

A century later, the housing crisis has not only persisted but worsened. The convergence of diverse housing vulnerabilities have affected people from all walks of life.

Renters, for instance, are facing rent increases double that of inflation, alongside evictions and displacement.

Homelessness is on the rise, disproportionately affecting Indigenous and Black people, gender minorities, and persons with disabilities.

Homeownership is increasingly precarious. Over one-third of Canadian households own a home with a mortgage, and of those, two-thirds have trouble meeting their financial commitments.

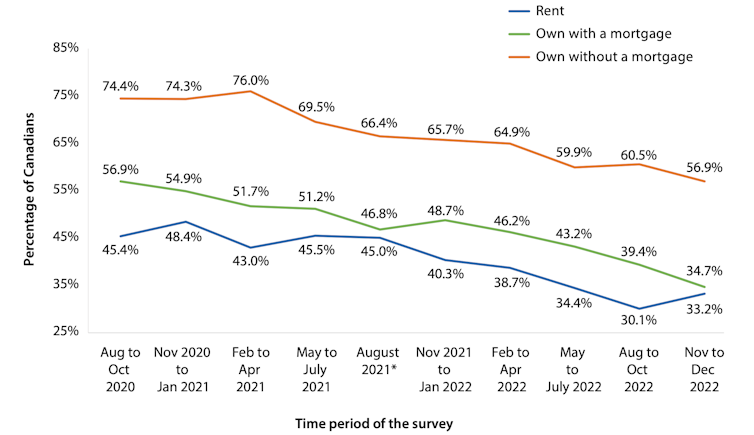

Decreasing percentages of both homeowners and renters can meet their financial commitments without any problems. (Financial Consumer Agency of Canada)

As a result, many Canadians have had to sacrifice privacy, comfort, stability, and location, leading to hidden housing vulnerabilities like undesirable living conditions, overcrowding and dissatisfaction.

Many young adults are now delaying homeownership, staying in their parents’ homes longer, postponing starting families or relying on parental financial support to buy homes, which can widen intergenerational wealth gaps.

How did the housing crisis happen?

These issues stem from policies in the 1980s to restructure the housing system, cultivating a culture of homeownership and market supremacy.

Canada had a strong housing welfare system in the 1960s and 1970s, but this changed in 1993 when the federal government stopped funding social housing programs. It shifted toward a commodified system that emphasized individual responsibility.

This shift was driven by two neoliberal beliefs. The first is that the private market is the most efficient way to provide housing, with the idea that older homes will become affordable as newer ones are built in a process called filtering.

In reality, older houses can become more expensive because of renovation costs and speculation, and affordability is tied more to land than property values.

The second belief is that homeownership promotes autonomy and reduces reliance on governments by building property assets, although the reality defies this belief.

Consequently, public divestment has created a siloed and marginalized social housing sector that now makes up about four per cent of the total housing stock. It primarily serves as a last resort for the “deserving poor,” like those with complex housing needs. The concentration of poverty and vulnerability in this sector further reinforces the stigmas around it.

Housing financialization has intensified since 1999 when the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) shifted from building homes to insuring mortgages. CMHC’s mortgage securitization programs expanded access to mortgages, fuelling demand and real estate speculation, turning housing into a vehicle for asset-building and capital accumulation. Federal subsidies further encouraged homeownership.

Homeownership rates rose from 63 per cent to 69 per cent between 1991 and 2011. Meanwhile, median house prices increased by 142 per cent, while incomes grew by only seven per cent. Household debt soared, with debt-to-income ratios rising from 109 per cent to 173 per cent between 2002 and 2017. Homeownership rates have since started to fall.

Why does the current system fail?

Neoliberal housing policies foster landlordism. Across British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, one in five residential properties are used as investments rather than primary residences. This financialization of rental housing, including short-term rentals, has strained long-term rental markets.

Economic pressures resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, rising construction costs, an aging workforce and population growth have worsened housing affordability.

Yet, the housing crisis is an inherent feature of a neoliberal housing system that created a tenure hierarchy, with homeownership at the top and non-market rental at the bottom. Everyone is expected to participate in the private market to climb the housing ladder from renting to owning.

Such a system will always fail to produce equitable housing outcomes. The market is most likely to respond to the housing needs of those with strong purchasing power, leaving behind low and moderate income families whose housing needs cannot generate effective market demand. The consequence is growing housing inequality, with many low-income families trapped in precarious living conditions.

Politically, the expansion of homeownership incentivizes electoral support for policies that prioritize homeownership and appeal to “homevoters.” Homeownership ideology is therefore reinforced and housing vulnerability becomes effectively “deadlocked.”

Current housing policies

Recent housing policy efforts have shown a renewed alignment between different levels of government in tackling housing challenges.

The federal government’s 2017 National Housing Strategy (NHS) focused on increasing rental supply, providing rent assistance and reducing homelessness.

The 2019 National Housing Strategy Act established access to adequate housing as a human right. The 2024 Canada Housing Plan aims to create 3.87 million homes by 2031 while recognizing tenants’ rights for the first time and protecting tenants’ tenure security.

Provincial governments followed suit. B.C.’s 2018 Homes for B.C. plan, for example, included measures to curtail non-resident investor speculation and boost market and non-market housing supply. It also established legislation to curb short-term rentals, end single-family zoning and increase density near public transit.

Municipalities implemented measures to cut red tape, streamline housing development, incentivize densification (like Montréal’s inclusionary zoning by-law) and standardize housing design and construction.

More action is needed

These policies signal a positive shift toward acknowledging housing as a human right and recognizing tenants’ rights. Renewed funding has supported rental housing construction, including co-op housing. Programs for community housing and homelessness are also pivotal for sustaining the aging social housing stock and supporting those in greatest need.

However, most policy approaches remain market-driven, prioritizing private developers and market supply. Of the NHS’s $115 billion budget over 10 years, 57 per cent is loans and under 40 per cent is budgetary expenditures with a small proportion to support community housing.

The biggest finance program, the Apartment Construction Loan Program, has mainly benefited private developers building above-market-rate housing.

Mortgage securitization programs remain central to the federal government’s financing of homeownership. The 2024 Housing Plan continues to expand mortgage access.

Market supply may help moderate affordability, but the impact will be limited without policies to grow the community housing sector. It also leaves deeper housing vulnerabilities unaddressed.

Homelessness has increased since the NHS launch. An estimated seven-fold funding increase is needed to halve chronic homelessness. Advocates have been calling for at least a doubling of the community housing sector, but a significant shortage persists.

Breaking the housing crisis deadlock requires breaking the hierarchy between homeownership and rentership, and between the market and non-market rental sectors. De-commodifying and de-financializing housing is key. This means expanding community housing, prioritizing community-based solutions and ensuring long-term security for all.

Yushu Zhu – Assistant Professor, Urban Studies and Public Policy, Simon Fraser University

Hanan Ali – Assistant Researcher, Housing Policy, Urban Studies Program, Simon Fraser University

https://theconversation.com/whats-behind-canadas-housing-crisis-experts-break-down-the-different-factors-at-play-239050

Tags: economy, housing, ideology, jurisdiction, participation, rights

This entry was posted on Wednesday, November 6th, 2024 at 9:55 am and is filed under Debates. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed.

6 Responses to “What’s behind Canada’s housing crisis?”

|

Recent Comments

Recent Comments

The Best Loan Firm

Reflection.

The housing crisis will impact on my future as a social service worker by, dealing with clients who are currently affected by the housing crisis. This issue is one that relates to most aspects of social work because many have this current issue. Homelessness is on the rise because of rising rents and the lack of affordable housing. The housing crisis feeds the homeless crisis. Which connects to a whole lot of other problems like mental health issues, addictions, crime etc.. As a future social service worker, I see this problem and want to help with it, but I can see that it is very hard because there is not enough housing for everyone, especially ones that are affordable. There are subsidized housing, but people have to meet a requirement to get them, but can’t meet those requirements. I have a question for anyone reading this, When we say that food, water, clothing is a basic need. What about housing? Is a home, a place to call your own a basic need or is it not. How come others get to have a home, whilst others don’t. Society treats certain people a certain way because the “system wouldn’t function”. We live in a broken world, and as a future social service worker I plan to help put it together piece at a time and it all starts with giving someone a chance or even a 100 chance.

The housing crisis will impact on my future as a social service worker by, dealing with clients who are currently affected by the housing crisis. This issue is one that relates to most aspects of social work because many have this current issue. Homelessness is on the rise because of rising rents and the lack of affordable housing. The housing crisis feeds the homeless crisis. Which connects to a whole lot of other problems like mental health issues, addictions, crime etc.. As a future social service worker, I see this problem and want to help with it, but I can see that it is very hard because there is not enough housing for everyone, especially ones that are affordable. There are subsidized housing, but people have to meet a requirement to get them, but can’t meet those requirements. I have a question for anyone reading this, When we say that food, water, clothing is a basic need. What about housing? Is a home, a place to call your own a basic need or is it not. How come others get to have a home, whilst others don’t. Society treats certain people a certain way because the “system wouldn’t function”. We live in a broken world, and as a future social service worker I plan to help put it together piece at a time and it all starts with giving someone a chance or even a 100 chance.

My reflection on this article,

I am a future social service worker, and The Housing Crisis will definitely affect my future career in a variety of ways. I live in Sudbury, Ontario, and we experience high rates of homelessness due the lack of housing around here. I have been afraid of becoming one of the many people who don’t have a place to call home, with the rising costs of living it is next to impossible to find a place to live. Currently, I am living in a co-operative housing complex, and have been for the past 18 years (That’s my whole life.) With my own experience with The Housing Crisis, and the statistics given in this article I have a better understanding on how to navigate this crisis in my future clients lives.

I want to become the change in not only this country, but this world as this affects everyone everywhere. I understand that no matter which branch of social services I end up working in, I know that this crisis will always have an affect on my career. While I know I don’t have the power to change this crisis myself, I know I have the voice to fight for change to The Housing Crisis from every single political level. I know to use and encourage people to usw their voices, and for the voiceless I plan to be the voice so they can be heard.

That’s what my goal is in life. To better the lives of the people and make sure they are heard.

My reflection to the article.

I believe that this issue will come up quite often in my future as a Social Service Worker. Especially if we keep going down this path to where things aren’t being fixed or at least looked at and taken seriously. The number of families and individuals who are losing a safe and secure home is only rising each year that this crisis persists on, leaving them to become homeless and in need of help. Having a better understanding that this doesn’t just exist in Sudbury alone and that it spans across the entirety of Canada. Reading this article and doing my own research on the matter has given me an insight on what this will look like for my future, as a Social Service Worker, in whatever field I end up in, this issue will arise. Having a better understanding of it will make my job not necessarily easier but allow me to look into different ways to get the help these individuals and families need to have a roof over their heads, whether that be looking into their budgeting, if they are in need of assistance through government funded programs and/or if they can find cheaper places to stay that are more affordable for them. What I want most is to make sure that whoever I am helping, I want them to feel safe. I believe that when people have a place to call their own, it does give them a sense of security and helps with their mental health. This can make for a more positive life, and also turns someone’s life around in a good way.

My reflection,

The Housing Crisis in Canada will impact my life as a social service worker because, Homelessness is something that happens on a day to day basis and something I have personally gone through when I was younger, I wasn’t completely homeless I had a place to go but I would bounce around every night with my mom, brother, and sister trying to find somewhere to call home. No matter where I was I never felt truly comfortable. I’m hoping to learn more and help overs with finding proper homes. I want to be the change and I want to help. I think the housing crisis in Canada will impact all social workers not just me, with homelessness becoming more of a problem everyday because of the housing crisis there will be tons of people coming in looking for help and a home, there are promises of new houses being built and for the sake of social workers in Canada I really hope they build more houses soon. My goal at the end of this program is to work with the homeless population which means housing is going to be a big part of my job not only housing but also shelters. Without a stable place to stay it is my job to help them find a place to call home and that’s what I plan on doing, I want to be able to help not only homeless people but also people struggling in poverty, because growing up I lived in poverty and I understand how hard it is to make ends meet. Not only was it hard for my mom but also for my siblings and myself. Sometimes we didn’t know when are next meal was going to be, I don’t want to see children suffering through that seeing that I went through it myself it’s hard and also draining for the parents working day and night to be able to provide. So if I’m able to take off some of that stress, and be able to help the parents and children in need I will. In conclusion there is a lot of things about housing that will affect me as a social service worker, that’s why I plan to be apart of the change, fighting for funding and fighting for the people and community’s that deserve more.