[Editor’s note: Today begins a four-part series drawn from All Together Healthy: A Canadian Wellness Revolution, the new book by Tyee veteran reporter Andrew MacLeod that challenges assumptions about health spending in B.C. and across the nation. To read an interview with MacLeod about his book, which is published by Douglas & McIntyre, click here.]

If you fail to follow the advice, well, you’ve made your choice.

This perspective ignores decades of evidence that most of what determines a person’s health is beyond the individual’s control. It individualizes the problem, implying that if you are fat, diabetic or sick, it’s your own fault.

The message that health is solely an individual responsibility is reinforced by disease advocacy groups. The website for Diabetes Canada, for example, promotes diet, nutrition, exercise and managing your weight. It includes lifestyle tips and makes clear who it sees as responsible: “Taking care of your health should be your top priority.”

There is, however, abundant evidence that type two diabetes, which accounts for 90 per cent of cases, is closely tied to income. As Dennis Raphael, a health policy and management professor at York University in Toronto, put it in a phone interview, “Even if poor people exercised and their weight was in the so-called ‘normal’ range, they’d still be two to three times more likely to get diabetes.”

And yet a search last year of the Diabetes Canada website for the word “poverty” returned just one document, a press release noting that Nova Scotia’s 2017 budget included $2 million to begin addressing poverty.

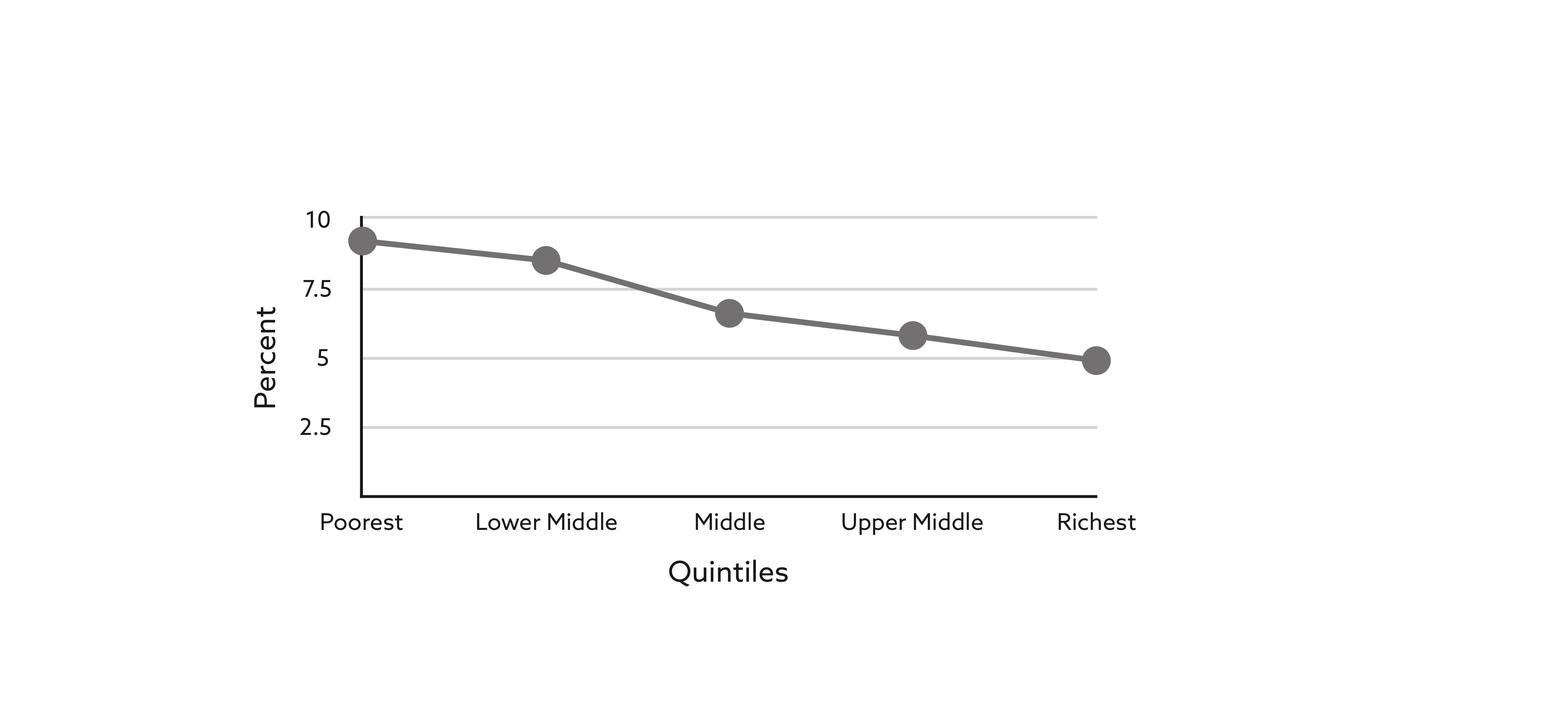

There’s little acknowledgement that at each step down the income ladder the chances a person will become diabetic increase.

The problem is that for most people, for most diseases, knowledge isn’t enough. Staying up to the minute on all the latest health information is daunting and may not provide the hoped-for benefits.

There are much larger forces underlying the choices individuals make that have a much larger effect on how healthy we are as a people. Often described as the “social determinants of health,” these forces play out across populations, providing an answer to the question of why some people appear to make worse choices than others, and pointing towards why some people are healthier than others.

_________________________________________________________________

Take the example of J. Gary Pelerine, who at 58 years old had for a year been fighting cancer that had first appeared on his tongue. It was only his latest setback.

“You got no idea what my luck’s been like in my life. Of course I’ve got cancer,” he said. He’d recently dropped 35 pounds due to the illness and was fighting to get the government to add a nutritional supplement to the disability assistance money he received. Over the course of an hour he smoked several cigarettes. None of the medical people had linked the cancer to smoking, a pleasure he’d had for 40 years, he said. If they had, it likely wouldn’t have made a difference.

“I got one enjoyment in life and it’s smoking,” he said. “That’s the only thing I do in life. I don’t care. I got nobody to come home to. If it’s going to kill me, I don’t give a shit. I honestly don’t give a shit.”

The story of his life included becoming a parent while still a teenager himself, divorce, estrangement from his children, a workplace back injury, hearing loss from working on loud job sites, and a suicide attempt. It started with a childhood lived in poverty in New Glasgow in northern Nova Scotia. “I grew up shithouse poor. I mean poor,” he said, drawing out the “poor” to stress just how poor he meant.

“I used to get off the school bus sometimes, change out of my school clothes into my hunting clothes, and if there wasn’t a rabbit in one of my snares when I got home, back from my trip through the woods, there wasn’t anything on that fucking table for dinner that night, buddy.”

There were four kids in the family and he was working on a farm baling hay by the time he was fourteen. Pelerine wasn’t blaming anyone for how his life had turned out, describing it as a long run of bad luck, but he observed, “My life was fucked before it started.”

It’s true that many people make choices that they know are bad for their health. It’s also true that everyone comes from somewhere.

‘Little or no progress’

In a 2015 report, the Canadian Institute for Health Information found that despite heavy spending on health care there was still a persistent health outcome divide between rich and poor. “Over the past decade, little or no progress has been made in reducing inequalities in health by income level in Canada,” it said.

For example, in all but the highest income group, people were rating their mental health lower than they had in 2003. Infant mortality continued to be tied to income as well, the report said. “If all families had experienced the same low rates of infant deaths as those in the highest income group, there would have been 300 fewer deaths in 2011.”

Obesity continued to grow in every province and at all income levels, but with continued gaps between rich and poor, particularly for women. “Women in lower-income households continue to have a prevalence of obesity that is 1.5 times higher than that among women in higher-income households (20 per cent versus 13 per cent),” the report said.

While most Canadians had reduced smoking since 2003, there was no change in the rate among the 40 per cent of adults in the bottom two income levels. Among people under 75 years old, those in the highest income group were less likely to be hospitalized with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease than they had been in 2001, but the rate of hospitalizations had risen for lower-income Canadians.

Where there’s smoke

Smoking is the leading cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and both smoking and hospitalization for the disease are more prevalent among people who are poorer. According to the CIHI, “the smoking rate is almost twice as high for the lowest-income Canadians as for the highest-income Canadians, and the COPD hospitalization rate is more than [three] times as high for the lowest-income Canadians compared with the highest-income group.”

Put another way, not only are poorer people more likely to smoke, they are more likely to get sick from it. It’s a phenomenon that epidemiologist Michael Marmot and physician Fraser Mustard described this way a couple decades ago:

“Those few men in the higher grades who smoked were at lower risk from smoking-related diseases than were smokers in the lower grades, though at each grade (with the exception of the bottom grade), smokers were at higher risk than nonsmokers. Smoking does kill; but it is clearly not the main explanation for the social gradient in mortality.”

According to the CIHI report, hospitalization for COPD is generally considered avoidable, and those who receive effective chronic disease management and primary care have a better hope of staying out of the hospital, which is where savings are to be had. On average, a hospitalization for COPD costs $8,000, it said. “If all Canadians experienced the same low rates of hospitalization for COPD as the highest income earners, there would be more than 18,000 fewer hospitalizations, which translates into $150 million in health sector savings annually.”

The CIHI’s report argued that major progress on health inequities was unlikely without taking a broader social approach, including boosting people’s incomes. Lower taxes and cuts to social assistance in the mid-1990s had contributed to a widening gap, it said.

The report suggested various ways to reduce income inequality, including increasing taxes and transfers, increasing minimum wages, acting on poverty reduction strategies and spending on education and training programs.

In Canada, however, successive governments have short-changed those programs for years. Juha Mikkonen and Dennis Raphael at York University wrote in 2010 that Canadian governments were offering protections and supports that were well below what would be available in other industrialized, wealthy countries. They used figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development comparing its 30 members:

“Canada ranks 24th of 30 countries and spends only 17.8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) on public expenditures. Among OECD countries for which data is available, Canada is amongst the lowest public spenders on early childhood education and care (26th of 27), seniors’ benefits and supports (26th of 29), social assistance payments (22nd of 29), unemployment benefits, (23rd of 28), benefits and services for people with disabilities (27th of 29), and supports and benefits to families with children (25th of 29).”

What Justin’s father was told

After the Liberals were elected in 2015 on a platform that promised increased social spending, it seemed likely that the broad approach to supporting a healthier population would be revived. After all, a series of reports by the federal government linking improved social conditions to better public health date back to one written in 1974 for the national health and welfare minister for Justin Trudeau’s father Pierre when he was prime minister (see sidebar).

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made Jane Philpott, a doctor representing Markham-Stouffville in Ontario, the health minister. There’s no question she came to the job with a better understanding than most health ministers about what it is that makes people healthy. In 2014, when her daughter Bethany was entering medical school at McMaster University in Hamilton, Philpott wrote a blog post offering 30 pieces of advice based on her own experiences as a doctor, which included nine years working in Niger. She wrote:

“Remember what really makes people sick and what makes them well. You will be taught about immunology, pathology, infections, and much more. But you already know that the social determinants of health actually set the stage for all those biomedical actors… Do your part to influence those social determinants. Speak up when you see the impact of poverty, unemployment, violence and more.”

You would think that as health minister, Philpott would have been ideally placed to act on that knowledge. But in his mandate letter to Philpott, who held the position for the first two years of the government’s mandate, Trudeau emphasized her job supporting the health care system. “Your overarching goal will be to strengthen our publicly-funded universal health care system and ensure that it adapts to new challenges,” the letter said. In doing so it gave priority to the system, not health.

Philpott was to work with provincial and territorial governments “to support them in their efforts to make home care more available, prescription drugs more affordable, and mental health care more accessible.”

As for public health, Trudeau wanted Philpott to increase vaccination rates, eliminate or reduce the amount of trans fat and salt in processed foods, restrict the advertising of unhealthy food and drinks to children, and improve food labelling.

The words “social determinants of health” were unmentioned.

In an interview last summer, York University professor Raphael sounded discouraged by the signals out of Ottawa. “I don’t see any evidence at all that anything’s getting better,” he said. “I’m not in a good mental space in terms of us moving this forward.”

Today’s Canada, in other words, matches the one described by sociologist and former federal health minister Monique Bégin in her 2010 forward to Social Determinants of Health: The Canadian Facts:

“The truth is that Canada – the ninth richest country in the world – is so wealthy that it manages to mask the reality of poverty, social exclusion and discrimination, the erosion of employment quality, its adverse mental health outcomes, and youth suicides.

“While one of the world’s biggest spenders in health care, we have one of the worst records in providing an effective social safety net.

“What good does it do to treat people’s illnesses, to then send them back to the conditions that made them sick?”

It’s a simple question, massive in its implications. Will Canada’s leaders ever address it forthrightly by shifting spending and policies? Back in 2010, the former health minister Bégin already sensed pressure building:

“Following years of a move towards the ideology of individualism,” she wrote, “a growing number of Canadians are anxious to reconnect with the concept of a just society and the sense of solidarity it envisions. Health inequities are not a problem just of the poor. It is our challenge and it is about public policies and political choices and our commitments to making these happen.”

https://thetyee.ca/Solutions/2018/09/04/Biggest-Health-Factor-Ignored/?utm_source=weekly&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=040918

Recent Comments

Recent Comments