In early 1997, Jamie Tanis Gladue pleaded guilty to fatally stabbing her boyfriend in Nanaimo. She was sentenced to three years in prison.

Her case led to a Supreme Court of Canada ruling that was supposed to change the way Indigenous offenders are sentenced.

But more than two decades later, Canada still lacks a consistent system to ensure this is happening.

In 1996, the Criminal Code was amended to add a requirement that judges consider “all available sanctions, other than imprisonment” for offenders.

The same section said courts should pay “particular attention to the circumstances of Aboriginal offenders” in deciding on a sentence. The changes recognized that crimes could not be separated from the effects of residential schools and other damage done to First Nations, and that Indigenous people were dramatically over-represented in prisons.

But that over-representation has now increased to all-time highs. Statistics Canada reports that in 2016/2017, 30 per cent of people taken into provincial custody and 27 per cent of those taken into federal custody were Aboriginal, although they only comprise 4.1 per cent of the population.

And incarceration rates for Indigenous people actually increased dramatically from a decade earlier, when the comparable rates were 21 per cent for provincial prisons and 20 per cent for federal penitentiaries.

Gladue, whose mother was Cree and father Métis, was sentenced a year after the Criminal Code amendments came into effect. But the judge, in part because she lived outside of a First Nations community, did not consider her Indigenous ancestry in passing sentence.

Her lawyers argued that broke the law, and appealed the case to the Supreme Court of Canada. She lost, and the appeal was dismissed. But the court agreed the judge was wrong to not take her history in account as an Indigenous person.

The judge who imposed the sentence “does not appear to have considered the systemic or background factors which may have influenced the accused to engage in criminal conduct, or the possibly distinct conception of sentencing held by the accused, by the victim’s family, and by their community,” the court ruled.

The Gladue ruling was considered an important step toward reducing Indigenous incarceration rates and encouraging restorative approaches to justice traditionally used in Indigenous communities.

Yet despite the ruling, there is still no consistent, effective approach to considering the special circumstances of Indigenous offenders in Canadian courts.

Some provinces and territories now use what’s known as a Gladue report to supply judges with information on the lives of Indigenous people before they are sentenced, including their individual circumstances, issues in their communities and the broad effects of colonialism.

Others still struggle to ensure Indigenous offenders’ sentences reflect their special circumstances.

And a few are even going beyond Gladue reports.

In Ontario, adding ‘after-care’

Ontario was the first province to accept the importance of preparing a complete Gladue report. The Ontario reports provide courts with a long, written history of a person’s life, including factors which speak to trauma they’ve experienced. The ultimate goal is to identify issues they struggle with and find possible solutions.

The judge can then use the report to develop an appropriate sentence, mixing options like substance abuse treatment, wellness programs, counselling and community service work with jail time.

Ontario recently added a key piece by adding Gladue “after-care” to the process, so offenders actually have help following through on the requirements of their sentence.

Shannon Nicholas is a Gladue after-care worker for the Akwesasne First Nation in southeastern Ontario, working with clients, service providers, probation officers and sometimes lawyers.

“It’s been our experience that they have so many recommendations, or so many probation requirements and restitution orders and mandatory orders, they leave the court and don’t know where to start,” said Nicholas, part of the Akwesasne Nation.

Nicholas is the first after-care worker in her community, and the program only started a year ago.

Clients appreciate the support, she said. “They’re all special… they all need to be heard and understood, and a lot of them just need to know how to help manage their life, or see that there’s light at the end of their tunnel,” Nicholas says.

Gladue reports help identify offenders’ needs, says Nicholas, and note both strengths and weaknesses. The after-care support helps offenders look at their lives objectively and navigate the system.

“For some, it’s getting them on methadone and maybe starting a reduction, because they’ve never tried to get sober before, and for some, it’s ‘Oh, I got my kids back.’ Anytime I can help anyone accomplish something it makes me feel good,” she added.

Some clients refer to her and her co-worker as “auntie” because the two lovingly scold them when they’re not meeting their potential, she said.

Jonathan Rudin is the program director for Aboriginal Legal Services of Ontario, the largest provider of Gladue reports in the province. It was the first organization to prepare a Gladue report and was involved with the precedent-setting Supreme Court case. ALS, like the Akwesasne program, receives funding from the Ministry of the Attorney General, as well as Legal Aid Ontario.

Additional funding in the last three years has allowed Aboriginal Legal Services to increase after-care activities. While after-care services don’t cover the entire province yet, they are making headway, he said.

“I think the need has always been recognized. Gladue writers write the report, and they make recommendations about sentencing options, and the judges often say, ‘Those are good ideas…’ but clients often need help doing the things they’ve been asked to do,” he said. “If they were easy, they would have been able to do them before.”

After-care workers can help with issues as simple as getting ID, or a health-care card needed to enrol in a substance abuse treatment program, he said.

That kind of small barrier can prevent people from getting treatment and put them in violation of their probation and at risk of being taken into custody again, said Rudin.

Rudin believes Ontario is the only province or territory with Gladue after-care workers, though other jurisdictions, like Nova Scotia, are beginning to look at the possibility.

The lack of federal funding is a major barrier to ensuring a consistent, effective response to the Gladue requirements across Canada, he said. Each province is forced to use some kind of “ad hoc” method of meeting their responsibilities.

“We do get some federal funding,” said Rudin, “but it’s less than 10 per cent of our overall budget. And other programs in Ontario don’t receive any federal [support]…. Some do, but many don’t.”

“I don’t think it’s solely a federal responsibility, but I think the federal government has a role in helping to deal with it,” he added.

The East Coast steps up

Nova Scotia has recently opened the first Gladue Court in the province and what may be the first Aboriginal Wellness Court in the country in the Wagmatcook First Nation on Cape Breton Island.

Judge Laurie Halfpenny-MacQuarrie helped drive the initiative when a court near Wagmatcook was closed, leaving members of the First Nation with a long, difficult commute to deal with legal matters.

Halfpenny-MacQuarrie had seen people pleading guilty just so they didn’t have to travel again for further court hearings, she said. She blames socio-economic factors for many of the problems Indigenous people have with the criminal justice system, as the Gladue ruling recognized.

The new approach in Wagmatcook is increasing access to justice, she said.

“In that facility, we have a courtroom, a day office for Nova Scotia Legal Aid, a day office for Nova Scotia public prosecution services, two interview rooms for private counsel, a full holding cell with two cells, an office dedicated to the Mi’kmaw Legal Support Network, a sentencing circle room, and we have a probation office room,” she said. It’s rare for people to be able to access all of those justice services in one building, she added. (Mi’kmaw Legal Support Network writes the Gladue reports ordered in the province.)

The Gladue Court is used for matters which would likely result in little or no jail time, while the Wellness Court is used for someone who has a long criminal record and may be facing a long stay behind bars.

The Wellness Court helps come up with a “treatment plan” including options that would be similar to those found in a Gladue report, and the entire process may take up to two years, she said.

If offenders don’t finish the treatment program, they can be returned to Gladue Court for sentencing, she said. “But if they do everything that’s asked of them, then they apply and fill out the exit application, and we have a graduation ceremony,” said McQuarrie.

Typically Crown prosecutors acknowledge the offenders’ progress and reduce or rescind sentences, she noted.

“Section 718.2(e) of the Criminal Code says it’s mandatory to take into account the historic treatment of First Nations people in Canada, and look for the least onerous sentences we can,” she said, adding that it also applies at bail.

“I’ve had many First Nations people over the years thank me in court for ordering the Gladue report, and for listening. Not just reading, but listening to what was being recommended, and for giving them a chance,” she said.

Some provinces not preparing reports

While Ontario has a comprehensive approach, and Nova Scotia is innovative, other provinces and territories are lagging.

The Alberta government has a partial system. It assigns Gladue reports on a contract basis to writers, though it doesn’t cover all areas of the province, and there is no after-care.

The Legal Services Society of BC does the same, but this year received additional funding from the province to increase the number of reports it can do, as well as provide university-accredited training to writers.

In Manitoba, probation officers prepare the reports, while Legal Aid Manitoba will step in and write reports for Legal Aid clients who feel the probation officer’s report is inadequate, a Legal Aid Manitoba representative said.

In Prince Edward Island, as well as Nova Scotia, the Mi’kmaq Confederacy takes care of the reports.

In Quebec there is a system for preparing Gladue reports, but it’s new and some judges appear to be resistant or lack understanding of Indigenous issues, said Sonia Gagnier, a court worker for Native Para-Judicial Services of Quebec, which assists Indigenous people dealing with the criminal justice system.

Gagnier, who writes Gladue reports as part of her role, said training is an issue for report writers.

In Nunavut, Legal Aid lawyers provide Gladue-related information verbally in courtrooms, according to a Legal Aid representative. In the Northwest Territories and New Brunswick, the information is included in the pre-sentence report written by probation officers.

In February, the Yukon government launched a $530,000, three-year pilot project to develop a Gladue report writing program.

In Saskatchewan, offenders and their lawyers hire privately contracted individuals (who charge thousands of dollars) to write Gladue reports.

And in Newfoundland, the situation is bleak.

“The situation with Gladue reports is probably as woefully inadequate as it is in every other province. There are very few reports being done. We would love to see more done, but there is not any person or organization in this province which is actually set up to do Gladue reports,” said Nick Summers, CEO of the province’s Legal Aid Commission.

“When a Gladue report is done, it’s almost always done by a probation officer or a parole officer… and at best, it’s a cut and paste out of Wikipedia,” he added. What should be a complete community profile, for example, is just copied from an online source without information on how the offender was affected by community life. The colonial history portion is the same, Summer said.

Get out of jail free card?

One look at the comments under any story about Gladue reports shows how inflammatory the issue can be. One of the most frequent criticisms is that it’s a “get out of jail free card” for Indigenous offenders.

That’s wrong, says Jane Dickson, a professor of law at Carleton University in Ottawa.

“Gladue is definitely not a ‘get out of jail free card… ’ because first of all, the Gladue requirements are simply one among a number of factors or principles the court has to take into consideration when they pass a sentence,” she said. “And they’re not a more important factor in law than any of the other sentencing requirements.”

If a person is sentenced and doesn’t receive jail time, it isn’t solely because of a Gladue report, Dickson said. It’s because all the information that came before the court was considered by the judge. Other considerations include community safety, deterring others from committing the same crime and making a public statement about the wrongfulness of the act.

Right now, Dickson is undertaking a massive research project on Canada’s Gladue practices in each province and territory. She confirmed that while some areas have fully equipped Gladue programs, other places have nothing at all. She expects the study to be completed next spring and hopes the result will give a clearer understanding of what’s happening now, and offer ideas for improvement.

Looking at offenders as people

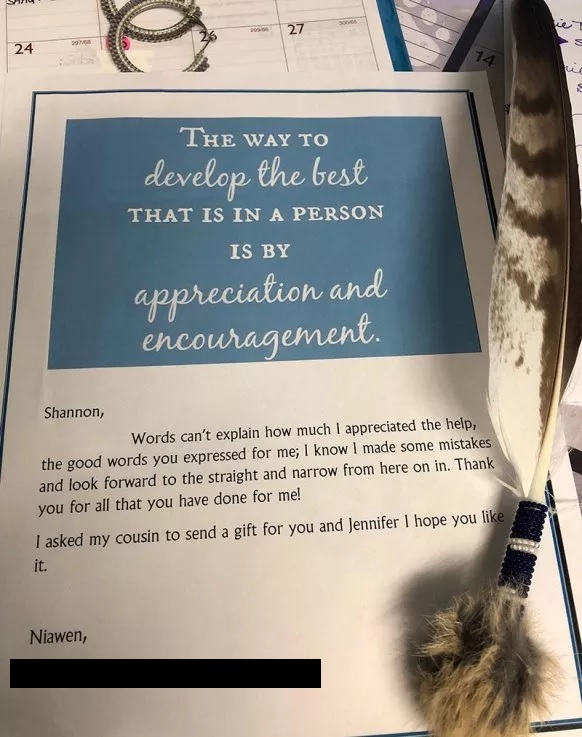

When Shannon Nicholas was asked about her most memorable case in her time in Akwesasne, she paused and then gazed at a hawk feather sitting on her desk.

“I’m looking at this hawk feather…. There was this incarcerated individual, who was going up before the national Parole Board and he was doing exceptionally well in the facility he was in. He got his Gladue report and we went into the parole hearing with him,” she said.

“We all spoke, and when it came time for him to speak, he started to cry,” said Nicholas.

Nicholas was shocked. As they wondered why the man was crying, he opened up about what he was feeling.

“He said, ‘I read my Gladue report, and this is the first time anyone’s ever said anything good about me… ’ He had never had any positive validation about who he was. He always heard the negative of everything,” she said.

“It was so powerful in there… I was crying, the Gladue writer was crying, his wife was crying, he was crying saying it… even the two older gentleman who were on the parole board were crying,” she added.

The parole board not only granted the man day parole, but told him as long as he did well while in the halfway house he was about to be released to, he wouldn’t have to come back to ask for full parole. It was guaranteed, as long as no conditions were breached. The hearing that day was also done in a traditional manner, in a circle with First Nations Elders present.

“It was a little bit of being human inside the institution, where you’re dehumanized,” Nicholas added.

A month later, she came to work and found a decorated hawk feather and a letter sitting on her desk — a thank you note from the man whom she helped.

https://thetyee.ca/News/2018/11/21/Failing-Indigenous-Offenders/?utm_source=weekly&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=261118

Recent Comments

Recent Comments