The idea of a Green New Deal—a radical and comprehensive transformation of the economy to cut greenhouse gas emissions while tackling inequality—has been gaining steam over the past few decades as an organizing principle for the environmental and social justice movements. But it wasn’t until 2019 that the GND exploded into the mainstream. Democrats in the U.S. Congress brought the idea to widespread public attention when they introduced a resolution on a Green New Deal last February. Although it never became law, the resolution galvanized U.S. activists and resonated around the world with its progressive rationale and blueprint for ambitious legislative action.

In Canada, the Pact for a Green New Deal, a large and growing citizens movement, brought together thousands of Canadians at more than 150 town halls across the country last year to explore a GND for Canada. Recommendations and next steps are expected in 2020. Most recently, Peter Julian of the federal New Democratic Party introduced a Green New Deal motion in Parliament. It is a concise and transformative legislative framework for a sustainable and inclusive Canadian economy.

What does a Green New Deal look like? Different advocates have advanced several visions, but the general principles are more or less the same in each:

- We face a climate crisis that requires rapid, global decarbonization, chiefly but not exclusively through the replacement of fossil fuels by cleaner energy sources.

- We face an inequality crisis that requires massive redistribution of income and wealth, and the political power it buys, away from an entrenched elite and toward citizens.

- Canada remains a colonial state that was built on and still facilitates the expropriation of Indigenous lands and livelihoods. Genuine reconciliation with Indigenous peoples will require the transformation of federal–Indigenous relations in line with principles enshrined in the UN Declaration of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

- Any just transition to a more sustainable world must be accompanied by a hopeful, inspirational vision for the future that includes good jobs, vibrant communities, widespread social and economic well-being, and general good times all around.

The details matter, of course, and there are many questions that GND advocates have yet to think through or agree on. For example, how can we produce enough electricity to rapidly replace all fossil fuels if we preclude new, large-scale hydro and nuclear projects in our communities? Where will we mine the environmentally harmful resources necessary to produce lower-emission technologies? Will new, green jobs be good, unionized jobs that are accessible in the places where jobs are needed most?

Furthermore, how will we pay for it all? Although inaction will be more expensive in the long term, the price tag of any Green New Deal in the short term is in the trillions of dollars for Canada alone. Even with unprecedented public spending, governments do not currently have the capacity to fund this transition in full, which means private capital needs to be incentivized or coerced into action.

The good news is we needn’t start from scratch. GND advocates, such as Naomi Klein, the U.K. economist Ann Pettifor, and a host of bright, young U.S. socialists including Kate Aronoff, Alyssa Battistoni, Thea Riofrancos and Daniel Aldana Cohen, among others, have laid out a number of workable answers, including many that are featured in the Alternative Federal Budget the CCPA co-ordinates each year with dozens of partner organizations and activists.

For example, both the AFB and GND crowd have called for cracking down on tax havens, tax loopholes and fossil fuel subsidies to help fund a transformative social and environmental agenda. Public banks, increased carbon taxation, green bonds and steeper deficit financing are other AFB mainstays that double as GND options for accelerating the just transition.

All these commonalities—in particular the GND’s insistence on democratizing our economies and using the climate emergency as a catalyst to rapidly roll-out new and enhanced, socially equalizing public services—got us seeing the Alternative Federal Budget, now in its 25th year, in a brand new light. Was the AFB a proto–Green New Deal in the making? Or, more proactively, can we make use of alternative budgeting to develop the detailed fiscal plan that will make the GND a reality in Canada?***

Twenty-five years ago, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives joined forces with the Winnipeg-based Cho!ces coalition to draft the first Alternative Federal Budget (AFB). There were two main objectives to the exercise, according to John Loxley, an original co-ordinator of the AFB and first chairperson of Cho!ces. The first was to demonstrate that “there are, indeed, alternative approaches to economic and social policy.”

Budgets are not merely legers to be balanced by skilled fiscal technocrats; they reflect the values and ambitions of the people who put them together. At the dawn of a new decade, in which the actions of governments will decide whether we succeed or fail to confront the climate emergency, those choices have never felt more important.

A second, related goal of the AFB was to build popular support for progressive alternatives to government austerity and to show how they are fiscally achievable. This was especially important in the project’s early days.

An anti-deficit delirium had set in across Canada in the 1990s based on overblown fears about the country’s debt and a one-sided debate about how to reduce it. Then finance minister Paul Martin’s insistence on cuts—to government services and programs, to provincial transfer payments, to public sector wages—as a way to shrink Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio was, we argued, a choice, not an inevitability. To prove it, the 1995 Alternative Federal Budget modelled a scenario where the deficit was reduced to 3% of GDP (the government’s own target that year) while social spending was maintained or increased in some areas.

Much has changed in Canada since those days, some of it for the better. Canadians are less inclined today to believe political rhetoric about the alleged menace posed by government deficits, for example. Many analysts suggested the Liberal victory in the 2015 election may have been attributable, at least in part, to Trudeau’s promise to run deficits to pay for his party’s “Real Change” platform. Although the NDP was calling for many fair tax reforms advocated by the AFB, which would have allowed the government to redistribute Canada’s wealth toward sustainable job growth, the party’s determination to appear “fiscally conservative” backfired. The Canadian public was apparently willing to incur relatively higher deficits if it meant bigger spending on social services and infrastructure.

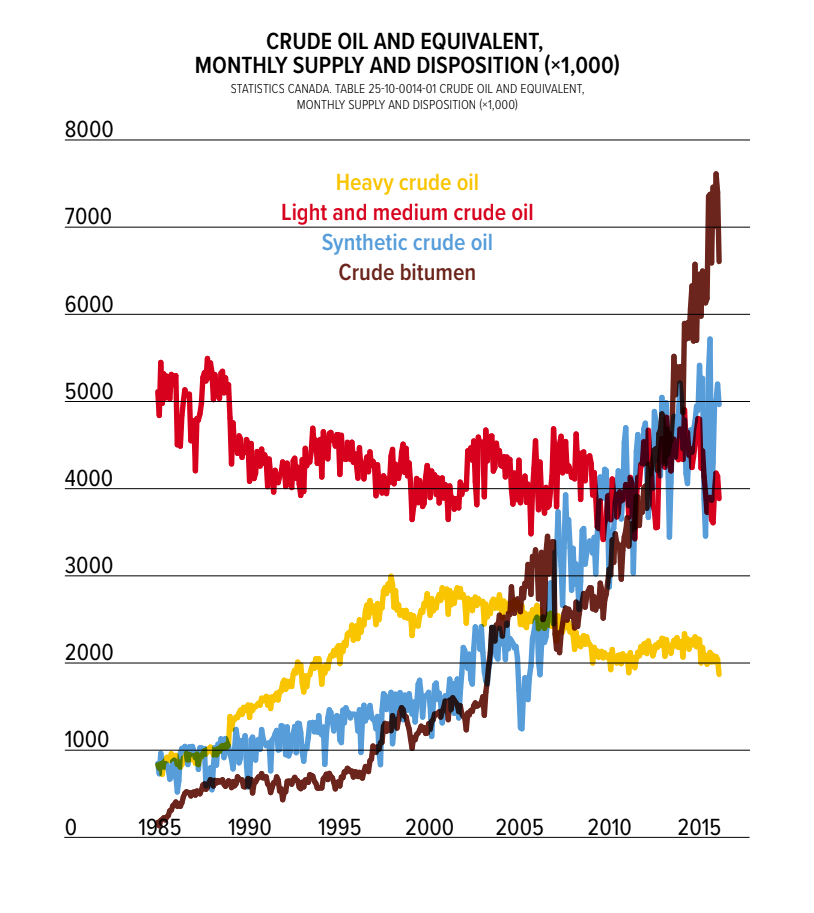

Circumstances, and priorities, have also changed in more fundamental ways since the deficit-slashing 1990s. The Mulroney government had been a key player in the development of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). But it and subsequent governments ignored commitments to bring greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions down to 1990 levels by the year 2000. Then starting around that year, consecutive governments actively supported (with subsidies and other measures) a rapid expansion of heavily polluting tar sands oil production and worked to undermine U.S. and European actions that might threaten this trajectory.

At a low point for Canadian politics, the Harper government likened Canadian climate justice activists and Indigenous communities who opposed new fossil fuel infrastructure to foreign-funded terrorists. The violent RCMP crackdown on Wet’suwet’en land defenders and their allies in early February, which included the suppression of press freedom, are a sign of how entrenched this dangerous and deluded attitude has become within the Canadian state.

Source: Statistics Canada Table 25-10-0014-01, Crude oil and equivalent, monthly supply and disposition (x 1,000).

Global inaction on climate change has resulted in a situation where, according to the IPCC, we now have less than a decade to cut GHG emissions in half, on a path to net zero emissions by 2050, if we are to avoid the worst impacts of the climate emergency. Considering the herculean effort entailed in decarbonizing the Canadian economy, the days of humdrum, fiscally balanced budgets may need to be put behind us indefinitely.

And contrary to the popular narrative in Canada, we are not the reckless first movers, sticking out our necks while the rest of the world clings to the status quo. Across the globe, governments and political movements are raising their climate ambitions. The European Commission recently unveiled a trillion-euro investment plan to decarbonize the European Union by 2050. New Zealand and others have committed to phasing out fossil fuel production entirely. In the United States, Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders has proposed spending US$16.3 trillion (84% of GDP) on a Green New Deal to reach 100% renewable energy for electricity and transportation by 2030 and full decarbonization by the 2050 target.

***

Given the scale of today’s challenges, it is extremely disappointing that our government still manages its revenues and spending much the same as it did when we launched our first AFB 25 years ago. Modest federal deficit spending aside, the assumptions driving budgetary decisions are locked in the past.

New revenues from economic growth have been used to cut taxes for businesses and wealthier Canadians when that money could have further enriched measures and programs to reduce inequality, eradicate poverty and meet the climate emergency head-on. The government’s first action in this post-election parliamentary session was to spend a further $6 billion a year on another “middle class tax cut” that leaves, at most, $15 a month in the pockets of people who will barely notice it.

There have been promising social investments since 2015—in housing, child care, arts and culture, and infrastructure, among other areas—and commitments to seeking equity for Indigenous, racialized, LGBTQ2S+, disabled and other historically marginalized communities. There have also been some steps taken to make Canada’s tax system fairer and more fiscally sustainable, such as the closure of income-splitting loopholes that mainly benefited Canada’s highest-income earners, and enhancements to the Canada Revenue Agency’s ability to go after corporate and high-wealth tax cheats. These and other measures, notably the Canada Child Benefit, have been mainstays of the AFB for years.

However, as long as this government holds firm to an ideological belief that incentivizing private sector–led growth and finding “market” solutions is always preferable to government-led progress, we will remain needlessly constrained in what we can do to create good, sustainable jobs and help the most vulnerable among us.

The federal carbon tax is a good thing, for example. But why is there no solid plan to use the revenues to fund sustainable, emissions-reducing public infrastructure (e.g., free public transit), or to help workers in the fossil fuel sector and their communities make a just transition to a decarbonized economy? Why is municipal access to the new $200 billion infrastructure bank contingent on private sector co-financiers making a 7–9% profit on their investment?

The reason is simple. A quarter-century of neoliberal dogma, much but not all of it enforced in binding international trade treaties, has succeeded in limiting both the imagination and real policy flexibility of decision-makers. Our governments are either encouraged or required to choose from an ever-narrowing array of acceptable fiscal and economic options that have, over the last three decades, increasingly privatized prosperity and socialized risk and debt.

By now most Canadians are familiar with the graph showing stagnating real (after inflation) wage growth alongside runaway income gains at the very top. If little has been done to lower greenhouse gas emissions (Argentina’s Esperanza Antarctica station announced a record-breaking temperature of of 18.5 degrees Celsius on February 6—see photo), even less is going on to counter our age’s outrageous levels of inequality. A decade after the biggest financial crisis of our time, banks and tech giants are raking in record profits and, in many cases, avoiding paying any taxes at all.

The current mood is now one of deep skepticism for the status quo, not just in Canada but across the globe. Parties who fail to respond are being voted out of office and chanted into submission by mass demonstrations (see the feature in this issue by James Clark).

The effectiveness of fake news may be as much a symptom of disenfranchisement as it is a statement of the power of new social media technologies; rising support for anti-immigrant populist messaging also cannot be disentangled from the widening social inequality of the neoliberal era. History shows us how quickly public dissatisfaction can turn to cynicism, and much worse, when enough people do not see their lives and priorities reflected in government actions.***

More than ever, the 2020 Alternative Federal Budget (out in March) is a blueprint for meaningful social engagement and positive change that both the federal governments and Green New Deal advocates would do well to consult. The ideas in its pages are good ones, the result of broad discussions between partner organizations with roots in frontline struggles for justice, equity and a just transition off fossil fuels.

“In creating these budgets,” explained Loxley in 2003, “activists learned about the possibilities and the limits of reform and gained greater credibility and confidence in agitating for social change and in opposing regressive government policies. This process of submitting policy ideas to a disciplined analysis in an open and socially inclusive forum represents a unique accomplishment.”

Following AFB tradition, our 2020 edition is not a “blue sky” wish-list for the government in power. The plan incorporates the government’s own economic growth and deficit forecasts so that we can show what more is possible even given the same constraints, whether or not they are real or self-imposed.

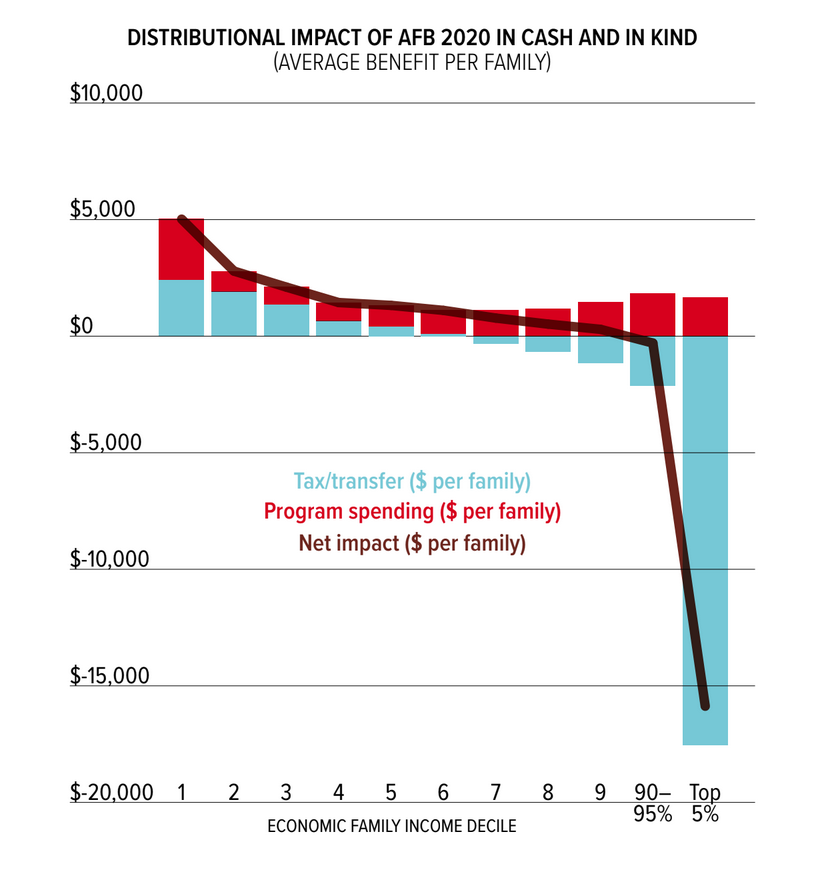

For example, where the Trudeau government has planned to run a $28-billion deficit this fiscal year, dropping to $18.5 billion by 2022-23, the AFB logs a slightly larger $42.5-billion deficit this year and a $20.5-billion deficit in 2022-23. We can do this while significantly expanding public spending by closing unfair tax loopholes, applying higher taxes to extreme personal and corporate wealth, and eliminating or diverting harmful spending such as the billions of dollars Canada spends annually on subsidies to the fossil fuel industry.

Still, at the end of the day, both the AFB and federal government maintain relatively low debt-to-GDP ratios of around 30% over the next three years. This conservative fiscal costing does not make the AFB plan any less ambitious, nor does it mean it can’t get us to where we need to be as envisioned in most Green New Deal scenarios.

In fact, according to our estimates, AFB 2020 would lift between 500,000 and 1.2 million people out of poverty (depending on how poverty is measured) in its first year and eliminate poverty outright within a decade. And it would substantially lower the cost of living for all but the wealthiest Canadians (see graph on this page). All this while restructuring the Canadian economy to dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions through a National Decarbonization Strategy that includes a clear timeline for the phase out of most oil and gas extraction by 2040.

The AFB vastly expands the availability of affordable child care, creating a universal pharmacare program, increasing the supply of affordable and supportive housing, and expanding mental health care services and services specifically targeted to older people. AFB 2020 reforms employment insurance, the Guaranteed Income Supplement and old age security payments so they deliver more in benefits to more people. Post-secondary tuition fees are eliminated, while the Canada Child Benefit, immigration settlement services and other rights and benefits are extended to everyone regardless of their immigration or citizenship status.

The AFB also pursues a just transition to a cleaner economy for those workers and communities most affected by ambitious climate policies, such as the phaseout of oil and gas production. We propose direct investment in hard hit communities to diversify the economy and create new jobs. The AFB also creates new funding to train new workers, especially those from historically excluded groups, for good jobs in the clean economy.

Canada’s history of colonialism and the state’s role in the genocide of First Peoples, its economic links to the North Atlantic slave trade, and more recent examples of state-sanctioned discrimination leave a long shadow. Official apologies alone are not enough. In addition to targeted social programs, better data collection on how racialized groups from all backgrounds—Black and African-diaspora Canadians, Indigenous peoples, new immigrants, etc.—are faring, as repeatedly called for in the AFB, can help us target and remove structural racism from our political and economic institutions.

Providing a transformative vision for the future that both acknowledges and challenges current political and economic conditions is especially important as the political salience of the Green New Deal grows. As the climate crisis deepens and the demand for alternatives swells, we can only expect the GND to attract more and more serious attention in the coming years. Advocates need a clear and practical agenda to make the most of this opportunity without sacrificing either environmental or social prerogatives. The AFB can help in this respect.

Adopting all the AFB 2020 actions would mark an important shift in government policy-making and put the Canadian economy on more inclusive and sustainable foundations. It would do so without significantly adding to Canada’s debt at a time when public debt is truly the least of our problems.

In that sense, the AFB shares many of the same objectives of the growing Green New Deal movement in Canada. It is our bold new deal for an uncertain new decade. We hope its ideas will inspire government action and embolden the public imagination about what it is possible to achieve when, in Loxley’s words, we begin “budgeting as if people mattered.”

Stuart Trew is Senior Editor of the Monitor and Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood is Senior Researcher with the CCPA’s national office.

https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/monitor/afb-meet-gnd?mc_cid=237b5141f9&mc_eid=26a8b9335a

Recent Comments

Recent Comments